Economic historians — and anyone who lived through it — will remember 2022 as a year of rapidly rising interest rates. From closely watched benchmarks like the federal funds rate to rates on mortgages, auto loans, and credit cards, the year ended with much higher rates than when it started.

Even if you pay your credit cards in full every month and don’t own a home or car, you feel the impact of rising rates in the broader economy. Growth slows, businesses pull back, wages stagnate, and unemployment rises. And if you do carry credit card debt or plan to apply for a mortgage or car loan, higher borrowing costs compound this newfound economic insecurity.

Things can get bleak, fast. But don’t feel like you’re a sitting duck in an economy that’s changing for the worse. You can’t control what interest rates do, but you can act now to protect yourself financially.

Interest Rates Are Going Up — Key Rate Changes Since January 2022

First, let’s see how key interest rates have changed since the beginning of 2022 and how those changes track with historic rate fluctuations.

Federal Funds Rate Over the Last 12 Months

The federal funds rate is a key benchmark interest rate set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), an executive body of the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States. It influences the rate at which banks lend to one another and indirectly affects interest rates charged (and paid) to consumers and businesses.

As you can see, the federal funds rate increased rapidly in 2022, from near zero in January to 4.25% in December (with further hikes to come).

This is faster than most previous Fed hiking cycles and brings up a crucial point about the psychological impact of rising interest rates. While it’s true the interest rate level matters — it costs more to borrow at 8% interest than 3% interest, after all — what’s even more important is the pace of the increase.

When rates rise nearly 5% in a single year, as they did in 2022, it hits differently than, say, 5% over four years. The faster the pace, the less time there is to prepare.

That’s why many consumers felt blindsided by the Fed’s unusually aggressive rate hiking pace in 2022, even though the federal funds rate isn’t high by historical standards. For perspective, here’s how the federal funds rate has changed over time, from its lows near zero during most of the 2010s and early 2020s to its high near 20% in the early 1980s.

You can see that while the federal funds rate has spiked dramatically on occasion, many hiking cycles were more gradual. And the magnitude of the most recent increase is unprecedented because it began with the federal funds rate near zero.

Still, from 1970 to 1990, the federal funds rate only briefly dipped below 5%, and typically, it was much higher. No one felt this persistently elevated benchmark more keenly than homeowners, who paid dearly for mortgage loans in the 1970s and 80s.

Mortgage Rates Over the Last 12 Months

By contrast, today’s homebuyers still have it relatively easy.

Sure, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate jumped from under 3% in mid-November 2021 to about 7% a year later. In percentage terms, that’s by far the fastest increase since the hiking series began.

But today’s seemingly sky-high mortgage rates are a bargain compared to the rates homebuyers paid back in the day. The 30-year fixed mortgage rate remained above 7% from 1971 until 1993. The 2022 mortgage rate maximum is just a few ticks higher than yesteryear’s minimum.

Let’s take a walk down memory lane and see why rates were so high for so long.

A spike following the energy crisis of the mid-1970s previewed a longer, more destructive period of rates above 10% from late 1978 into 1986. As is the case today, many would-be homebuyers delayed purchases during this period. Those who had no choice but to buy often chose riskier variable-rate mortgage loans, then took advantage of temporary rate pullbacks to refinance into lower-rate loans — despite the considerable cost and reams of physical paperwork required in pre-digital times.

The 30-year fixed mortgage rate spiked past 11% again in 1987, then began a long, mostly steady descent. This gave homeowners who bought amid eye-watering rates ample time to refinance, refinance, and refinance some more. By the mid-1990s, very few homeowners still had double-digit mortgage rates. America’s collective memory of that painful period began to fade.

Financial conditions would get better still for American homebuyers. Fixed mortgage rates briefly approached 9% in the turn-of-the-millennium economy’s irrational exuberance, but the subsequent recession brought them back down to earth. They remained historically low into 2004 and didn’t rise much afterward, setting the stage for the housing bubble that would trigger the next recession.

The aptly named Great Recession was the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. The Fed recognized the damage would take years to repair and kept the federal funds rate near zero into 2015. Its multiyear dance with the x-axis is clearly visible on the 68-year chart above. Mortgage originators made lemonade out of lemons as best they could, but growing competition from low-cost online lenders capped mortgage rates well under 5%, even after the Fed began raising the federal funds rate again. Add steady but not outrageous home price appreciation to the mix, and the period between 2010 and 2016 turned out to be a very good time to buy a house in America.

Noawdays? Not so much.

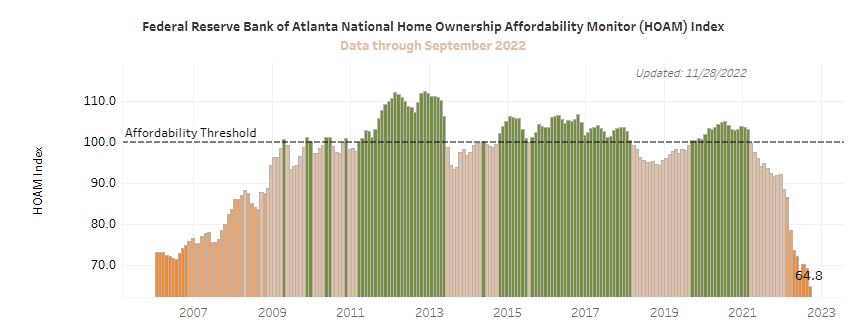

Today’s 6% to 7% mortgage rates might be moderate by historical standards, but they don’t tell the whole story. See, housing prices soared during the pandemic as homeowners and renters who could afford to trade up to bigger spaces did so. Coupled with rising rates, rising prices ballooned new homeowners’ monthly payments, putting homeownership out of reach for many. The Atlanta Fed’s Home Ownership Affordability Monitor fell off a cliff beginning in 2021 and now sits at all-time lows.

Auto Loan Rates Over the Last 12 Months

Long-term trends in auto loan rates mirror those in mortgage rates.

The average rate on a 48-month consumer auto loan meandered between 10% and 12% in the 1970s before hitting an all-time high of 17.36% in November 1981. The trendline’s first foray below 10% in 1992 proved durable — it hasn’t been that high since.

Today, the average auto loan rate is right in line with the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate. The 48-month auto loan rate in August 2022 (the most recent month we have data for) was 5.52%, near the 5.55% 30-year mortgage rate for the week of Aug. 25, 2022. This is notable because prevailing auto loan rates were a bit higher than mortgage rates for most of the 2010s and early 2020s. Unlike mortgage rates, pandemic auto loan rates never dove to sub-3% depths.

So car buyers aren’t facing rate shock, at least not yet. But they do still have to contend with an affordability crisis thanks to record-high prices for both new and used vehicles.

Credit Card Rates Over the Last 12 Months

Both mortgage and auto loans are secured by valuable assets: real estate and vehicles, respectively. That’s why we call them “secured loans.”

Credit card balances aren’t secured by anything other than the cardholder’s promise to repay, which though legally binding is difficult to enforce. You could argue that the likelihood of wrecking their credit score is reason enough to keep those credit card bills current. But many folks don’t think that far ahead (or they have bigger things to worry about when they fall on hard times).

As unsecured loans, credit cards are much riskier than mortgages or auto loans. Issuers charge higher interest rates to compensate for this added risk. Today, the average credit card rate (excluding 0% interest promotions) is well above 18% and will likely touch 20% before prevailing interest rates begin falling again.

Credit card users had it marginally better in the past, but carrying a balance has never been a good idea. Since 1991, the lowest average monthly credit card interest rate was 11.82% in August 2014. And that figure includes credit cards with 0% interest rate promotions. Exclude those promotional cards, and the series low rate was 12.42% in February 2004.

More recently, credit card interest rate trends have a “heads I win, tails you lose” vibe, with banks living it up in the winners’ circle. Credit card rates barely declined in 2020 even as the Fed slashed the federal funds rate to zero, but they’ve been going up like clockwork since the most recent hiking cycle began. You can bank on them ticking up yet again next time the Fed acts.

How to Protect Against Rising Rates

Interest rates haven’t stopped going up, and they’re not likely to fall significantly anytime soon. It’s not too late to make these moves to protect your finances.

1. Lock in Lower Loan Rates When You Can

A lighter-than-expected Consumer Price Index report for December 2022 all but confirmed what many keen observers already suspected: Inflation has peaked in the United States, at least in the short run.

That means the Federal Reserve’s long-awaited “pivot” away from aggressive interest rate hikes is nigh. If the economy slips into recession in 2023, as most economists expect, the Fed could actually lower interest rates.

Bond markets are already pricing in such a move. And because mortgage rates follow not just the federal funds rate but also key U.S. Treasury benchmarks, they’re falling in anticipation of easier money ahead.

But they won’t fall in a straight line. If future CPI reports come in hot, or other inflationary data or events spook bond markets, mortgage rates could spike again. So watch them closely and be ready to take advantage of pullbacks by refinancing your current mortgage to a lower interest rate while you can.

And if you have an adjustable-rate mortgage, be sure to refinance it into a fixed-rate mortgage before the introductory fixed-rate period ends (typically no more than 10 years after you get the loan, but usually more like five or seven years). You can leave that new fixed-rate loan in place for the next 15 to 30 years — unless rates fall even more and it makes sense to refinance again.

2. Pay Off Credit Cards

The data is unmistakable: When interest rates go up elsewhere in the economy, credit card interest rates rise too. This increases the cost of carrying credit card balances from month to month. If you already have significant credit card debt, it can do a number on your household budget.

So make a plan to zero out your existing credit card balances as soon as possible. If you’ve had limited success chipping away at them, take a more formal approach with the debt snowball or debt avalanche method. (No need to stop throwing spare cash at your balances when you can, though.)

And when your final payoff is in sight, right-size your budget so you’re not liable to slip right back into debt.

3. Trim Your Spending & Build Your Emergency Fund

“Right-sizing your budget” means reducing your monthly spending to a level significantly lower than your monthly take-home pay. Shoot for 5% lower to start, but don’t stop there. 10%, 15%, or even 20% could be feasible, depending on how much you earn and how much of it goes toward fixed or non-discretionary expenses like housing and utilities.

You can find savings in unexpected places, not just cliches like “cut out the morning latte” and “dine out less.” Shop around for better pricing on your auto and property insurance policies, for example, or take a hatchet to your ever-growing roster of subscriptions.

Use your savings to pay down debt at first. Once that’s done, start building an emergency fund to avoid taking on new credit card debt after a big unexpected expense.

4. Use 0% APR Promotions as You Can, But Pay Off Your Entire Balance Before Rates Reset

Higher interest rates reward savers and investors while penalizing borrowers. Unless it’s absolutely necessary due to an unexpected financial emergency or life change, don’t take out additional debt once interest rates start to climb

The one big exception: If you need to make a big purchase or need extra help paying down existing high-interest credit card debt, consider applying for a new credit card with a long 0% APR introductory offer on purchases or balance transfers (or both). Depending on the offer, you might have 18 months or longer from your account opening date to pay off early purchases or transferred balances.

Just remember to pay off your entire balance before the introductory period ends. Otherwise, you could be liable for deferred interest charges, as if the promotion never happened. Always charge or transfer less than what you feel you can afford to pay off, and if you worry you’ll be tempted to spend more when your card arrives, say “no thanks” to the offer.

5. Don’t Pay Off Old Low-Interest Loans Right Away

Because credit cards charge interest at variable rates tied to underlying benchmark rates, it’s even more important to pay down old credit card debt and avoid taking on more when interest rates are high.

The opposite is true for fixed-interest installment debt like home and auto loans.

Imagine you took out a mortgage at 3% interest when rates were low. Your savings account paid a paltry 0.5% interest rate, and you were too risk-averse to put your money in the stock market where the theoretical return would have been much higher.

The rational move in this scenario would be to pay down as much of your mortgage as possible — even paying off the whole thing early if you can. You’d lock in a guaranteed 3% return on those payments, much more than your savings account paid.

Fast forward a few years. Interest rates have risen. Now your savings account yields 4%, and you can invest your cash in equally low-risk investments that pay 5%, 6%, or more. It makes no sense to grab that 3% return when the money you’d need to do it could earn more elsewhere.

How to Take Advantage of Rising Rates

It’s not all bad news when interest rates rise. Make the best of a bad situation with these financial strategies for high-interest-rate environments.

1. Open & Fund a High-Yield Savings Account (or Increase Contributions to an Existing Account)

When interest rates rise, it gets easier to tell true high-yield savings accounts from pay-the-bare-minimum savings accounts.

True high-yield savings accounts raise their yields as the federal funds rate increases, though they’re not directly linked and the increase tends not to be point-for-point. Pay-the-bare-minimum savings accounts adjust their yields rarely, if ever. The best high-yield savings accounts pay 4% interest, give or take, while the others pay less than 1%.

Shop around for high-yield savings accounts at well-reviewed online banks, which tend to pay higher interest rates than brick-and-mortar banks. Look for banks offering new account opening promotions that can be worth hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

If you already have a high-yield savings account you’re happy with, find ways to trim your spending and boost your savings rate to take full advantage of the miracle of compound interest. Save an extra $1,000 per year at 4% interest, and you’ll net $40.

2. Build a CD Ladder

While interest rates are still on the way up, build a multi-CD ladder. It’s a flexible way to take advantage of the best CD offers amid rising rates without locking your money away for too long.

Let’s say you have $20,000 to invest. Instead of putting the entire 20 grand into a four-year CD yielding 4.5%, split it up into four buckets and buy CDs with shorter (but varied) maturities. For example:

- $5,000 in a six-month CD yielding 1%

- $5,000 in a 12-month CD yielding 3%

- $5,000 in an 18-month CD yielding 3.5%

- $5,000 in a 24-month CD yielding 4%

You have to hold your CDs until maturity. But if you expect rates to go up for a while — at least two years in this case — you can roll each over into a fresh, higher-rate CD.

Maybe the new six-month CD yields 3%, the new 12-month CD yields 5%, the new 18-month CD yields 6%, and the new 24-month CD yields 7%. Your total return with the CD ladder will be similar to your hypothetical return going all-in on the four-year CD, but you’ll preserve the option to tap some or all of the capital well before the four-year mark. And if rates start going down after the first or second year, you can always disassemble the ladder by cashing out each CD at maturity.

3. Buy Series I Bonds (I-Bonds)

A virtually risk-free investment yielding near 10%? Keep dreaming.

Log into TreasuryDirect and see for yourself. Series I savings bonds, better known as I-bonds, are U.S. government bonds designed to keep pace with inflation. Their rates reset every six months, in May and November, reflecting current inflation figures and expectations for the future.

From May to October 2022, I-bonds yielded 9.62%, beating even the best savings accounts by 6% or more. The rate reset to 6.89% in November, but I-bonds are still far more lucrative than savings accounts and short-term CDs.

I-bonds do have some important restrictions and limitations. You can only buy $10,000 worth per year, or $20,000 as a couple. You can’t cash them out for the first 12 months and face an interest penalty if you cash out before the five-year mark, so they’re best viewed as long-term savings. But if you have spare cash you can afford to tie up for at least a year (and ideally five), I struggle to think of a reason why you wouldn’t want I-bond exposure in a high-rate environment.

4. Consider Nontraditional Savings Accounts or Investments, But Use Caution

If your risk tolerance allows, explore nontraditional high-yield investments that can double, triple, or even quadruple returns on savings account deposits. But use caution, even with money you can afford to lose. You’re unlikely to benefit from FDIC insurance or even the less comprehensive protections afforded to stock market investors.

Many of these options offer exposure to real estate in some way:

- Real estate crowdfunding platforms such as Fundrise and Streitwise

- Public real estate investment trusts (REITs) that own portfolios of commercial, industrial, or residential real estate

- Hard money loans secured against real estate and publicly available oh platforms like Groundfloor

Bear in mind that real estate tends not to perform well when interest rates are high. Default risk increases on loans backed by real estate in high-rate environments as well. Still, returns on these savings account alternatives — and others not linked to real estate, like Save’s Market Savings account — are tempting.

Final Word

What goes up must come down. This too shall pass. Pick your cliche.

It might be cold comfort when inflation is roaring, your credit card balances are through the roof, and your homeownership dreams feel more out of reach than ever. But you don’t have to look too far into the past to find a time when interest rates were near historic lows. And few serious economists expect rates to remain elevated as long as they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Better times await.

In the meantime, there’s plenty you can do to protect yourself financially. Play your cards right with a new high-yield savings account or CD ladder, and you might even come out ahead.